A SHORTCUT TO MIX VOICE

When it comes to teaching someone to find their mix voice I’ve observed that I can often use a “short-cut” to get a singer there much faster: with some singers, all of the sounds and sensations I need them to feel are already present in their speaking voice – however, that particular coordination of the vocal cords simply isn’t accessed when they are singing.

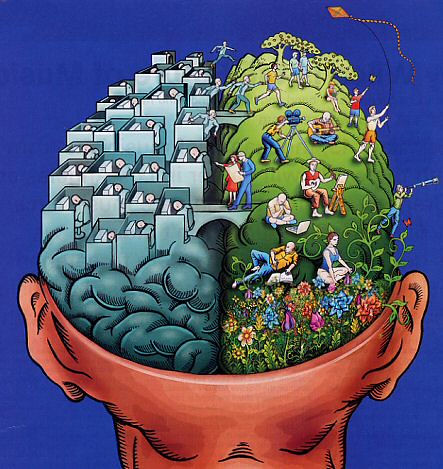

First, a little context: our “Right Brain” is where our musical abilities primarily live and so, when we’re singing, that hemisphere is dominant. When we are speaking, our “Left Brain”, or logical side, takes over. Interestingly, research has shown that stroke victims, when robbed of speech due to damage to their Left Hemisphere, can often be taught to use the singing ability still intact in their Right Hemisphere to communicate their needs – even while they are still unable to form spoken words. (Click here for article).

By using a spoken sound (with pitches ranging in the mix voice area) that is easy and free of strain, and technically in a mix coordination, I can take a voice through steps that incrementally build a pathway between the Left and Right Hemispheres of the brain, until they are able to physically coordinate that range in the same way, regardless of their dominant area of the brain. Sometimes, by the end of a first voice lesson, I can have someone singing strong in their mix voice for the first time.

I have to be sneaky about this “short-cut” in order to build a neural pathway between the two hemispheres. The nervous system will always resist the change at first because the brain’s job is to keep the status quo: when the brain senses we are trying to make changes to it’s neural programming, it will momentarily sabotage our efforts in defense of what it’s used to. My strategy is to go back and forth between spoken and sung sounds until they are able to make the same sounds in both contexts. These singers are always surprised to find just how easy and effortless it feels to sing in mix if they’ve never done it before. Then, since most singers assume (wrongly) that singing beyond chest voice has to involve a lot of strain and effort, I spend a lot of time affirming through vocal exercises that the strong, yet “too easy” sound is the right one.

This is not a trick I can use with every singer but I am surprised just how many people it works for – and I will say that it tends to work a little more often with female voices than with male voices. (There are reasons for this – send me an email if you’re curious).

There are some singers, of course, who have never experienced a mix coordination in their voice, whether speaking or singing. I, personally, was one of them. I had never spoken or sung pitches beyond my chest-voice that weren’t in a light head voice and so, had to take the long road and spend time building that coordination into my voice from scratch. For those singers like me, there is a very effective – though longer – journey to build a solid mix voice. Consequently, as a side-effect, once I was able to experience a clear, easy sound beyond my chest voice I found that my speaking voice became much healthier and I began to use much more vocal range to express myself in daily life.

Whichever path your voice is ready for – whether a short cut or the long way round – a healthy mix-voice is within your reach.